A New Era of European Defense, an EU Joint Army on the Horizon?

A Historical Overview of the EU Joint Army Implementation:

To fully understand the development of a joint defense idea throughout the history of the European Union, we must go far back in time, till 17 March 1948, when the Brussels Treaty was signed. At that time, the European Countries were weak, and the threat of the Soviets led to another period of uncertainty right after the end of WW2. The Brussels treaty established the WU (Western Union), which joined the countries of France and England, already bonded by the Treaty of Dunkirk, with the addition of the Benelux (Belgium, The Netherlands, and Luxemburg). The Western Union was an advanced military alliance that regarded collaboration in economic and political fields. But this setup lived shorter than expected. With the Czechoslovak coup d’état, the Italian Communist Party becoming more and more influential, and the beginning of the Cold War, the American anxiety over a shift in control over Europe led to the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty and the formation of NATO. Even if the relationship between NATO and EU countries is remarkably complex and will be analyzed deeper in the next paragraph, for now, we need only to know that it is an intergovernmental military alliance that, in 1949, included the five Treaty of Brussels states, as well as the United States, Canada, Norway, Portugal, Denmark, Iceland, and Italy. Furthermore, due to the political weight of the USA and the impracticality of both NATO and WUDO (the military arm of the WU), the WU layer of defense lost quite all its significance and importance, even dismissing its central headquarters of Fontainebleau in favor of the NATO alliance that completely took over responsibility for the protection of Western Europe.

Another milestone in our story is the ECD, the European Defense Community, born in the aftermath of the outbreak of the Korea war, from many perceived as the general test of a Soviet attack in Europe. The obvious option here was for West Germany to join NATO to avoid a similar conflict with its Eastern counterpart, but that would have involved West Germany having its army. For obvious reasons, the French weren’t too keen on this. So instead, in 1952, America and the French government proposed the European Defense Community via the Treaty of Paris. The ECD would have combined the armies of all the members of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC, the constituents were France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) into one super National command to form a political Union in the future. The French parliament, nevertheless, didn’t like the idea of giving up national control of their army and refused to ratify the Treaty in August 1954. However, this only led to the amendment of the Treaty of Brussels and the creation of the WEU (the Western European Union), an even less impactful form of the WU but with the addition of Italy and West Germany. In the end, West Germany ended up joining NATO in the 1960s. More than once, Charles De Gaulle tried to reform the European Economic Community (EEC) into a security alliance, in large part because he didn’t think that European and American interests always aligned. As such, he took France out of NATO’s command structure in 1966 and contradicted America by taking a pro-Arab stance in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. Unfortunately for De Gaulle, the EEC members preferred their American security umbrella in the form of NATO. His plans failed and ended up falling by the wayside for several decades. Only some minor reforms were taken, like the EPC (European Political Cooperation) as the initial coordination of foreign policy within the European Communities in 1970, or the Petersberg Declaration, a list of security, defense, and peacemaking tasks set out by the WUE.

But major enhancements arrive only in 1992, with the Maastricht Treaty that established the European Union. The reform added requirements on both common foreign and defense policies and was further strengthened by the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997. However, progress was slow, and it was simply with the 1998 Saint-Malo Declaration between France and the UK that the idea of a European defense identity gained traction, leading to the creation of the European Security and Defense Policy in 1999. In the Saint-Malo Declaration, we can find: “The Union must have the capacity for autonomous action, backed up by credible military forces, the means to decide to use them, and a readiness to do so, in order to respond to international crises.” claiming the willingness to regain credibility in the defense field, after the inadequacy of UE in the Kosovo War, where they failed to intervene to stop the conflict. Regardless, even in this scenario, the role of NATO remains more than central.

The Last steps were taken in 2007-2009 when the Lisbon Treaty was approved, which came after the failure of the European Constitutional Treaty in 2005. The new EU structure was far more complete than before and brought to the formation of The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), a central component of the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and of the European Defence Agency (EDA) which are still in place today. The CSDP, in the European commissions’ own words, offers: “A framework for cooperation between EU member states within which the EU can conduct operational missions with the aim of peacekeeping and strengthening international security in third countries, relying on several military assets provided by EU member states.” As only a framework, CSDP doesn’t actively or legally bind the EU military, just lets them discuss it. The closest thing that the EU has to an army is Frontex, formerly the European Border and Coast Guard agency. At its heart, Frontex has one key task: to protect Europe’s, or more precisely, the Schengen areas.

Finally, after Campaign Swipes by Trump, the relationship between the EU and NATO began to falter. The Trump administration’s declaration to cut its financial contribution to NATO gave new vital impetus to the joint European defense programs. Thus leading, in 2017, to the creation of PESCO, a permanent structured cooperation, that enhances the collective efforts of countries involved in the development of defense capabilities, shared investments in projects, and an overall improvement of the readiness of their armed forces. The last notable thing before jumping into the effect of the Ukrainian war on EU defense is the establishment of the European Defence Fund (EDF) in 2019, which deployed a budget of close to €8 billion for 2021-2027. €2.7 billion to fund collaborative defense research and €5.3 billion to fund collaborative capability development projects complementing national contributions.

The NATO-EU relationship:

The EU and NATO have become prominent global players when it comes to handling international crises of the past and present. The basis of this collaboration is both institutions’ common and shared values, norms, and principles. Their strategic partnership is built on coherence, transparency, and equality, which involves respecting the interests of EU Member States and NATO. This partnership has yielded fruitful results in areas such as political consultation, capabilities, terrorism, and cyber defense. However, despite these steps, there is still more room for improvement in the current EU–NATO connection.

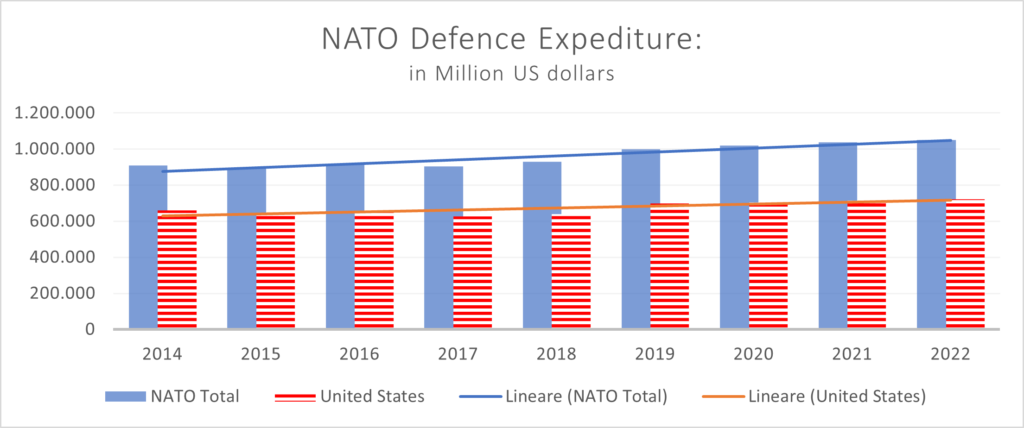

A good starting point to comprehend the NATO-EU relationship is a famous article published in the Financial Times in the aftermath of the Saint-Malo declaration. The secretary of state, Madeleine Albright, indicated in the so-called “three D” the Conditions to which European cooperation should be sought: no discrimination (towards other NATO members); no duplication (compared to resources and, in perspective, the functions of NATO); no decoupling (no scission between Atlantic safety and European security). From these words, we can understand the difficulties of having two symmetrical orders concerning supranational defense. Ever since NATO’s formation, European leaders have been worried that a European army or defense union would end up just copying what Europe already has under NATO and possibly even undermining NATO by annoying the Americans. European governments have also been more than happy to rely on the US and its massive defense budget for security guarantees or simultaneously cut their military spending. Another vision is that the United States would favor the development of a stronger European Common Security and Defence Policy. In particular, NATO will always need to work more and more together effectively with the EU defense institution. The CSDP, therefore, no longer stands in contradistinction to the trans-Atlantic relationship but, rather, should be one of its primary building blocks. For many researchers, a more coordinated EU defense institution, that can also culminate with an EU joint army, can positively impact the EU-NATO relationship. First, the future EU can achieve military autonomy and a more balanced relationship with NATO on a major burden-sharing basis. The achievement of these two goals has the potential to improve the United States’ relationship with the EU as the US has advocated for the EU to assume more responsibility in NATO’s defense efforts, which aligns with the EU’s objective of attaining a greater degree of autonomy. However, in recent years, the EU-NATO relationship has been shaken. The possibility of Trump’s withdrawal from NATO is a major concern, as it could catalyze the EU army vision to become a reality if he is reelected. Although Biden has reassured the world that this won’t occur, a future president like Trump could think otherwise and the EU can’t rely only on the election of a favorable American President. For these reasons, we can notice that EU countries are trying to depend less on US funding of NATO albeit the shift is particularly slow as shown in the graph.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Excel library: https://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2020/pr-2020-104-en.xlsx

The New Scenario after the Ukraine War:

First off, the NATO alliance after the second invasion of Ukraine in 2022 looks more relevant than in the last thirty years. The enlargement process due to the Russian danger made Finland join in April 2023, strengthening its defense capability. Another key factor that shifted after the Russian invasion was troop deployment. Last year NATO had less than 5,000 troops on the eastern border spread evenly across Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. Today that number is nearly 40,000 deployments predominantly concentrated in Poland, where NATO now has over 10,000 troops. Although it’s a justified reaction to put NATO’s troops on its eastern Front in response to the aggression in Ukraine, this behavior has risen tensions in Moscow at a time when neither side enjoys the prospects of a new Cold War. However, the war in Ukraine has not changed the order of US strategic priorities or its decision to focus on dissuasion against China in the Indo-Pacific, where their effort is also focused due to a potential invasion of Taiwan.

The EU reaction was noteworthy too. The establishment of the European Peace Facility (EPF) in 2021 had significant implications for the EU’s security and its partners. The EPF enhanced the EU’s capacity to safeguard the welfare of its citizens and collaborate with its allies in boosting security. It empowered the EU to furnish a diverse array of military supplies and security-related infrastructure to its partners, which have proven to be vital to providing Ukraine with defensive weapons. Furthermore, with the endorsement of a Strategic Compass that coordinates most of the actions of member states, from defense funding to arsenal production, EU member states are starting to develop more and more defense industries. These actions, on one hand, can bring cohesion and stability to the Unity while supporting Ukraine, on the other one, they started a new season of investment for countries like Germany, which were always reluctant to a strong rearming plan. This historical moment can easily bring the right spark to ignite the possibility of an EU joint army or, at least, a more integrated EU common defense.

Why implement defense cooperation:

Firstly, strengthening defense coordination enhances European strategic autonomy concerning foreign policy. This refers to the ability of the European Union to act autonomously in the global arena and to safeguard its interests and values. Strategic independence is also about diversifying and intensifying the EU’s strategic partnerships and reducing its dependence on other actors, particularly in areas such as defense and energy.

Another central flaw of our current EU defense system that must be faced, is the requirement for unanimous agreement among all European countries regarding foreign policy decisions, which grants each of the 27 EU members a veto. This poses a significant deterrent, particularly as an idea as ambitious as a European army has yet to be proposed, and some EU countries, like Denmark, have already publicly opposed its creation. The heart of the problem lies in the balance of power. If the European Commission were to exercise control over the military, the ultimate authority would reside in Brussels with the current President, Ursula von der Leyen. Alternatively, the creation of a new, independent military pillar within the EU would present the same challenge of determining who would administer it. However, such approaches could address the issue of how to utilize EU forces in a crisis without being subject to a veto, greatly improving the speed and effectiveness of strategic defense actions.

One of the foremost effects of a unified army would involve the defense industry. Without any doubt, joint armament production in the EU countries would bring clear advantages in terms of the economics of scale and scope. Some countries can even specialize in some sectors, like Italy in naval production or Poland in tank one. Nevertheless, defense investment can help Europe escape economic recession. The first reason is represented by the contribution to a country’s technological heritage. The relationship between research and development activities and revenues in the defense industry is about 8%. While it may not invest the most in relative terms, it is still a significant sector in absolute value, second only to pharmaceuticals in invested rates. This underscores the importance of funding defense companies, especially considering the increasing significance of dual technologies that can be applied to both military and civilian purposes. However, there is also the risk of a crowding out of resources, where capital expenses for other sectors may be penalized in favor of defense investments. Yet, the significance of crowding out is outweighed by the fact that defense investments have a strong multiplier effect on national income. In Italy, the multiplier for defense investments is one of the highest among all, standing at 1,83. That means an increase in GDP of 1,83€ for every 1€ invested.

Finally, if all European countries will match the already existing NATO agreement of investing 2% of their GDP on defense, the combined effort will lead to the EU ranking second on the global defense spending list, reaching 342 billion dollars in second place above China, with 293 billion, but significantly less than America with 801 billion. Though military spending isn’t the only meaningful indicator of an army’s military might, it holds considerable significance for the EU in terms of defense and military capability and would, with the second more financed army in the world, further solidify its status as a political superpower.

References:

Eu Security Policy, What it is, How it Works, Why it Matters by Michael Merlingen

European Security in NATO’s Shadow by Stephanie C. Hofmann

The European Defence Agency edited by Nikolaos Karampekios and Iraklis Oikonomou

Routledge Handbook on the European Union and International Institutions, EU-NATO Relation by Nina Grager, Kristin Haugevik and edited by Knud Erik Jorgensen and Katie Verlin Laatikainen

La difesa europea by Antonio Missiroli and Alessandro Pansa

Verso la difesa europea, l’Europa e il nuovo ordine mondiale by Domenico Moro

La Moneta e La Spada, La sicurezza europea tra bilanci della difesa e assetti istituzionali by Filippo Andreatta

On the way towards a European Defence Union – A White Book as a first step by the European Parliament’s Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Sub-Committee on Security and Defence.

The EU Common Security and Defence Policy by Panos Koutrakos

Europe’s Common Security and Defence Policy by Michael E. Smith

The SAGE Handbook of European Foreign Policy, volume 1, edited by Knud Erik Jorgensen, Asne Kallad Aarstad, Edith Drieskens, Katie Laatikainen, and Ber Tonra

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Excel library: https://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2020/pr-2020-104-en.xlsx

SIPRI, Military Expenditure Database https://milex.sipri.org/sipri

Alessandro Simonotti

CLEAM - a.simonotti@outlook.com